Enhancing behavioral health promotion through tailored comic books: When Nicotine Attacks-Fight the Crave

Enhancing behavioral health promotion through tailored comic books: When Nicotine Attacks-Fight the CraveFile

Okoli-Slides for Presentation.pdf

(1.52 MB)

Thumbnail Image

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

|

|

Parental barriers to seeking mental healthcare for Saudi children at risk of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderFile

KappiAPNAconference2021.pdf

(13.76 MB)

Thumbnail Image

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

|

|

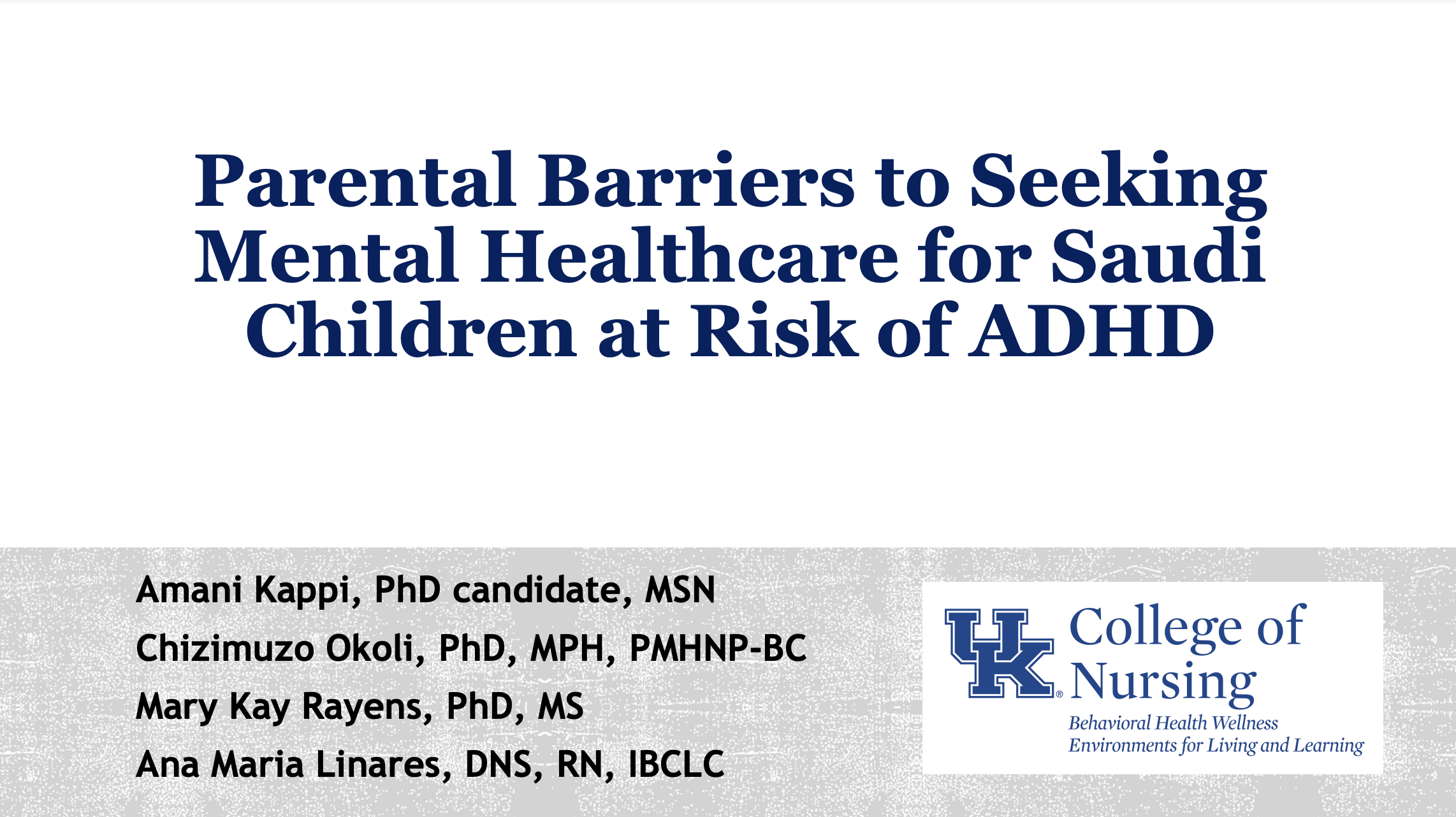

What is the relationship between the experience of trauma and substance use among healthcare workers?Healthcare providers (HCPs) are uniquely vulnerable to occupational trauma exposure due to the responsibility of caring for people in diverse settings. Thumbnail Image

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

|

|

Prevalence and factors of compassion fatigue among Chinese psychiatric nurses: A cross-sectional studyCompassion fatigue has emerged as a detrimental consequence of experiencing work-related stress among psychiatric nurses, and affected the job performance, emotional and physical health of psychiatric nurses. However, researches on Chinese psychiatric nurses' compassion fatigue are dearth. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the prevalence and factors of compassion fatigue among Chinese psychiatric nurses.All participants completed the demographic questionnaire and the Chinese version of Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL-CN). One-way ANOVA, t-tests, Levene test and multiple linear regression analysis were conducted to evaluate factors associated with compassion fatigue.A total of 352 psychiatric nurses in 9 psychiatric hospitals from the Chengdu, Wuhan, and Hefei were surveyed. The mean scores of compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress were 32.59 ± 7.124, 26.92 ± 6.003 and 25.97 ± 5.365, respectively. Four variables of job satisfaction, exercise, had children, and age range from 36 to 50 years explained 30.7% of the variance in compassion satisfaction. Job satisfaction, sleeping quality, and marital status accounted for 40.4% variables in burnout. Furthermore, job satisfaction, average sleeping quality, and years of nursing experience remained significantly associated with secondary trauma stress, explaining 10.9% of the variance.Compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress among Chinese psychiatric nurses were at the level of moderate. The higher job satisfaction, healthy lifestyle (high sleep quality and regular exercise), and family support (children, stable and harmonious marital status) positively influenced compassion satisfaction and negatively associated with burnout or secondary traumatic stress. Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

Published Date

|

|

From twisting to settling down as a nurse in China: a qualitative study of the commitment to nursing as a careerBackground: The nurse workforce shortage, partially caused by high work turnover, is an essential factor influencing the quality of patient care. Because previous studies concerning Chinese nurse work turnover were predominantly quantitative, they lacked insight into the challenges nurses face as they transition from university to their careers. A successful transition can result in new nurses’ commitment to their careers. As such, this study sought to understand how new nurses commit to the career and focused on identifying facilitators and barriers to such commitment. Methods: This was a qualitative study using a grounded theory design. Through purposive sampling, clinical nurses were recruited from hospitals in Western China to participate in semi-structured interviews. The data was analyzed through coding to develop categories and themes. Results: Theoretical saturation was achieved after interviewing 25 participants. The data revealed the ‘zigzag journey’ of committing to the nursing career. The emerging core theme was “getting settled”, indicating that new nurses needed to acclimate to the work reality in the nursing career. By analyzing the data provided by the participants, the researchers concluded that the journey to getting settled in nursing compassed four stages:1) “sailing out with mixed feelings”, 2) “contemplating to leave”, 3) “struggling to stay”, and 4) “accepting the role”. For most participants, nursing was described as a way to earn a living for their family, not as a career they felt passionate about. Conclusions: Committing to a nursing career is a complicated long-term process. There seems to be a lack of passion for nursing among the Chinese clinical nurses participating in this study. Thus, the nurses may need continued support at different career stages to enhance their ability to remain a nurse for more than economic reasons. External Link

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

Published Date

|

|

Social Smoking Environment and Associations with Cardiac Rehabilitation AttendancePurpose: Continued cigarette smoking after a major cardiac event predicts worse health outcomes and leads to reduced participation in cardiac rehabilitation (CR). Understanding which characteristics of current smokers are associated with CR attendance and smoking cessation will help improve care for these high-risk patients. We examined whether smoking among social connections was associated with CR participation and continued smoking in cardiac patients. Methods: Participants included 149 patients hospitalized with an acute cardiac event who self-reported smoking prior to the hospitalization and were eligible for outpatient CR. Participants completed a survey on their smoking habits prior to hospitalization and 3 mo later. Participants were dichotomized into two groups by the proportion of friends or family currently smoking ("None-Few" vs "Some-Most"). Sociodemographic, health, secondhand smoke exposure, and smoking measures were compared using t tests and χ2 tests (P < .05). ORs were calculated to compare self-reported rates of CR attendance and smoking cessation at 3-mo follow-up. Results: Compared with the "None-Few" group, participants in the "Some-Most" group experienced more secondhand smoke exposure (P < .01) and were less likely to attend CR at follow-up (OR = 0.40; 95% CI, 0.17-0.93). Participants in the "Some-Most" group tended to be less likely to quit smoking, but this difference was not statistically significant. Conclusion: Social environments with more smokers predicted worse outpatient CR attendance. Clinicians should consider smoking within the social network of the patient as an important potential barrier to pro-health behavior change. External Link

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

Published Date

|

|

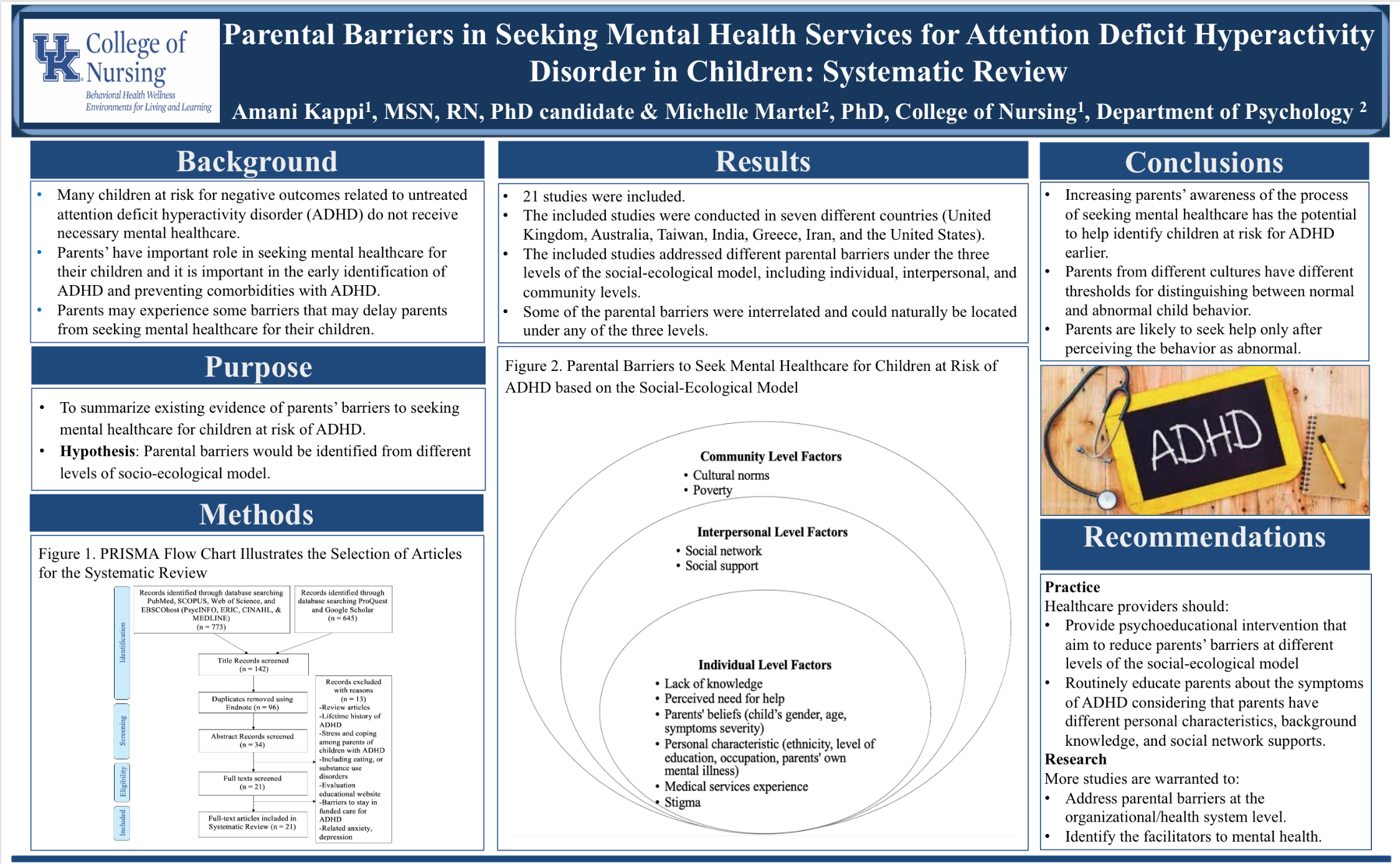

Parental Barriers in Seeking Mental Health Services for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: Systematic Review PosterPurpose: To summarize existing evidence of parents’ barriers to seeking mental healthcare for children at risk of ADHD. File

Amani.CCTS poster.pdf

(1.01 MB)

Thumbnail Image

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

|

|

Parental Barriers in Seeking Mental Health Services for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: Systematic Review |

|

|

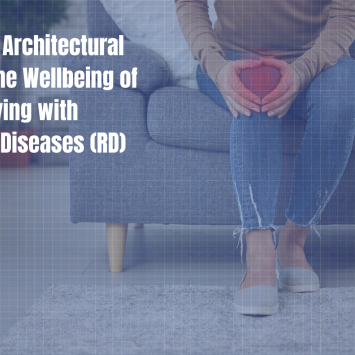

The Role of Architectural Design in the Wellbeing of Patients Living with Rheumatic Diseases.The Role of Architectural Design in the Wellbeing of Patients Living with Rheumatic Diseases.

Categories

Architecture plays an important role within the health sector. Architects are given the unique task of meeting traditional architectural standards for general construction while adhering to the distinctive needs of those who will live or work there. The nuances of this task are often heightened when meeting the needs of people with physical disabilities such as Rheumatic Diseases (RD). RD’s often involves painful joints, swelling, and inflammation. This creates challenges regarding an individual’s ability to work, manage their activities of daily living, and subsequently, maintain their overall independence. Patients living with RD can struggle with the likes of getting dressed and getting out of bed, and other tasks such as turning on a tap and opening a bottle cap. In fact, in a bulletin on musculoskeletal diseases, the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that,

Continue Reading TranscriptGiven that people living with RD almost always experience challenges with activities of daily living at some point, having a proper environment is critical to maintaining independence. A discordant environment can greatly impact their health and functionality. For contemporary architecture, a continued focus on the modern world without much attention to health implications can overshadow considerations for mobility and ease of living for individuals living with RD. Small environmental changes such as secure carpet edges, secure bathroom surfaces, well-placed handrails, and optimal lighting can go a long way to improve safety of the home environment. Cutting back on clutter can be useful as well; so, incorporating built-in storage would be useful. Carefully designed environments can improve the quality of life of people living with RD. Such environments can only be created if architects have the proper knowledge. An interdisciplinary approach is required that promotes a healthy balance of environmental awareness, health, and well-being. For example, studies on the value of physical activity and home exercises emphasize the need for adequate physical space. These spaces promote a conducive environment for those with physical disabilities to perform exercises that are necessary to maintain functional independence. This design element must be taught in the architectural education system. Although architectural students are taught to consider unique needs as given by American Disability Association requirements, the needs of people living with RD are not frequently addressed in architecture schools. If such lessons are added to the curriculum, the new generation of architects may have increased awareness of the importance of providing environments in which individuals living with RD can thrive. With such training, we can ensure the creation of a supportive architectural environment that encourages safety and independence for people living with RD.

ReferencesPunzi, L., Chia, M., Cipolletta, S., Dolcetti, C., Galozzi, P., Giovinazzi, O., Tonolo, S., Zava, R., & Pazzaglia, F. (2020). The role of architectural design for rheumatic patients’ wellbeing: the point of view of Environmental Psychology. Reumatismo, 72(1), 60-66. https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2020.1251 Briggs, A., Woolf, A., Dreinhöfer, K., Homb, N., Hoy, D., Kopansky-Giles, D., Akesson, K., March, L. (2018). Reducing the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2018;96:366-368. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.204891 Dimensions of Wellbeing

|

Post-Traumatic Growth Among Nurses: What are Influencing Factors?Examining posttraumatic growth (PTG) can yield insight to constructively understand and approach trauma among nurses. Data was analyzed from 299 nursing staff on traumatic experiences and resulting PTG. Work-place trauma resulted in the lowest PTG scores among nurses should be explored. File

Posttraumatic Growth APNA 2020.pdf

(1.06 MB)

Thumbnail Image

Document Category

Dimensions of Wellbeing

|